Up in the skies of the oceanic world, Ionis III, soars a fearsome wyvern, uncontested in its position of being at the top of the food chain. The Russet-Backed Skahl is the apex predator of a large chain of scattered islands in the southern Magellan Ocean, the planet’s largest ocean. Whenever its shadow falls, the creatures scatter in fear, knowing that death lurks above. With its powerful wings, the Russet-Backed Skahl glides effortlessly through the air, its crimson scales shimmering in the sunlight. Its name, “Skahl,” originates from an ancient local dialect, meaning “death from above.”

Evolutionary History

Skahls are found all across Ionis III but are typically small predators similar to a hawk or owl, living in the shadow of larger predators. Skahls have adapted to many different lifestyles, some hunt in flocks, some are carrion feeders, and others even live like seals or penguins. However, the Russet-Backed Skahl stands distinct as the largest and most impressive of the group.

Skahls as a group follow most of the anatomical norms of all Ionian life but do a few things very differently. The first life on Ionis III was trilaterally symmetrical, and most of the aquatic life still is. These two groups are known as the Trilatarians and Minlatarians (from Latin for “less,” minus) following the naming conventions for Earth life. Skahls, however, are actually members of the Trilatarian family, having been part of a second radiation out of the water and onto land, or in this case, into the air.

Early Skahl ancestors lived similarly to flying fish on earth, but more successfully. They used their huge fins as gliding surfaces, and their powerful tails as rudders. Thanks to the thicker atmosphere and more plentiful oxygen, plus some quirks in how Trilatarian lungs are structured, switching to breathing air was fairly easy. As air became easier to breathe and their fins became better and better at generating lift, early Skahls eventually switched from fish that could fly a little, to birds that were also powerful swimmers. Most Skahls still live in or near aquatic environments. Some species, however, have begun to find their way further inland, to fill flying niches left vacant after a recent mass extinction. No member of the Skahl family line has ever been fully terrestrial.

Anatomy

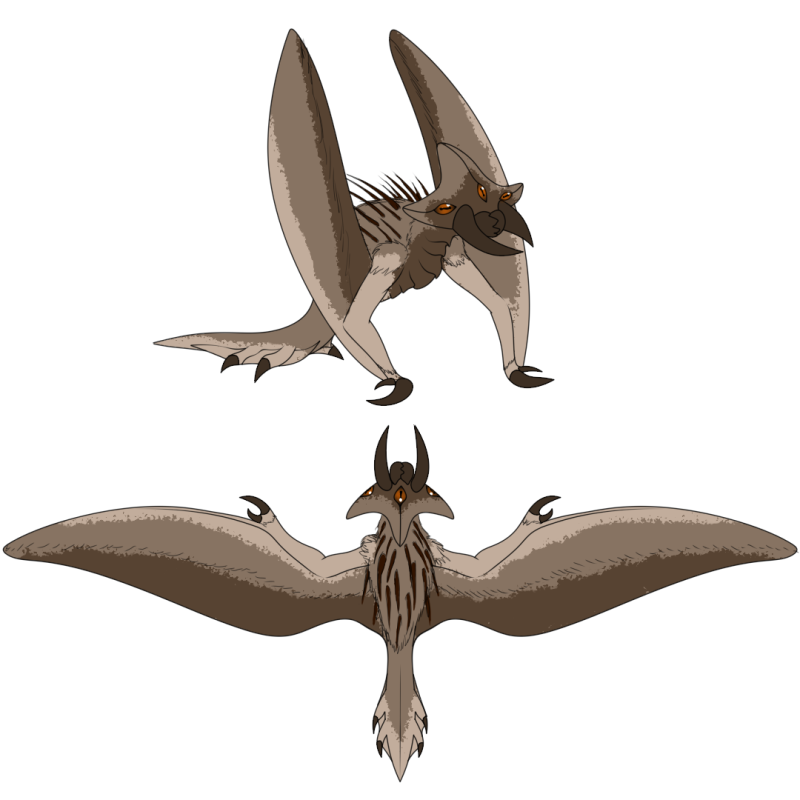

Skahl anatomy strongly resembles Minlatarian norms rather than Trilatarian, which makes it confusing. The head is shaped like a shortened letter T flipped upside down, with three eyes. One on each side, and a third above the mandibles. The third mandible was too poorly placed to use easily on land, so it has been reduced into a mere nub of bone that is hidden beneath the fur. They have lost the third set of limbs along their “spine,” since they had no real need for them and they were cumbersome in the air. Their other limbs have shifted upwards to sit equidistant on each side of the body. The forelimbs have developed into large, powerful wings, similar in structure to the wings of Earth birds. Each wing has a pair of claws that can be moved like fingers. These pseudo-hands are mostly used to walk but can be used to grip food and branches as well.

The rear two pairs of limbs are very reduced, having only been used to support small stability fins in the water. These fins have adapted into a gliding membrane, which generates extra lift and helps support the heavy tail. The tail itself is actually rather short, less than a foot long, but most of the torso has become thinner and longer, and the ribs have reduced into mere bone pebbles to add flexibility. In effect, everything behind the wings functions like a tail, with all internal organs shifted forwards to sit between the wings.

The body is covered in an integument that is similar to protofeather “fuzz,” but superficially resembles fur, hence the name. The fur on the back between the wings has formed into large bristles of a darker brown shade, which is what gives the species its name. The thick covering and brown shade allow the Skahl to blend into the brown-trunked tree analogs of the forests, where they spend their vulnerable juvenile years.

Life Cycle

Skahls lay their eggs in shallow pools and calm riverbeds in forests. Having only left the water about 150 MYA, their eggs still cannot survive on dry land. After hatching, Skahls stay with their siblings for the first nine months or so, approximately one Ionian year. During this time they survive by scavenging. Once a hatchling can hunt for itself, it leaves the group and lives alone until mating.

Skahls will usually become sexually mature at about two Ionian years of age, and reach adult size around the same time. At this point, they are almost double the size of any other flying Skahl, with a body length of 1.5-2 meters (5-7 feet) and a wingspan anywhere between 3.5-5.5 meters (12-18 feet). Most individuals will be on the lower end of this range, but since Skahls grow for their entire lives, some older individuals can push the limits for size.

When ready to mate, Skahls take a pretty passive approach. They head for the nearest suitable body of water and just hang around the area, hunting and living normally, until a member of the opposite sex arrives. They may wait months since Skahls are very territorial and do not often live near each other. When they eventually bump into a mate, they make up for their laziness with an impressive show.

They begin by making a barking call and trying to impress the other by flapping their wings and making a lot of noise. They need one wing to support their bodies, so their one-winged flaps are rather awkward. Then they progress to aerial stunts, diving towards the water from a great height and pulling away at the last moment, or sometimes even diving below the surface and then coming back up in one motion. The grand finale is an aerial battle, where both try to ram the other out of the air. It does not seem to matter who wins, only how hard they fight.

With that completed, the female lays her 8-20 eggs in the water, and the male fertilizes them. They then go their separate ways, and will not return to that pool for future mating. The hatchlings emerge about 5 months later, live their first few weeks in the water (eating mostly their own eggs) while their wings finish growing, then leave the water in a group to start looking for food.

Hunting

Skahls as a group employ many different hunting strategies. Some are small, nimble aerial hunters, some are large scavengers, and others hunt the same Trilatarian fish they descended from. Russet-Backed Skahls are different from most since they are the only major predator in their environment. Juveniles stay in forested areas, where the prey animals tend to be smaller and better suited for them. Their smaller bodies are nimbler and make quick pursuit of small prey easy. Once they reach adult size, they move to the open grasslands.

Adult Russet-Backs are not very agile fliers due to their large, heavy tails, which must be held flat and fairly still to use the gliding membranes, but they are exceptional long-distance gliders. An adult can cover up to 100 miles a day hunting. They roost in whatever trees or cliffs they can find in their territory, then set out for the day just after dawn. They glide slowly over the scrublands, watching for movement below.

Once they spot prey, they drop like a shadow toward it, trying to scare it into running. If it hides, the Skahl will typically move on to find easier prey. But if it has its prey on the move, the Skahl will stay close enough to be easily visible and occasionally will dart in to use a claw, mandible, or tail to keep it running. The goal is to force the prey to exhaust itself while the Skahl can easily glide for an hour without needing to flap once. When the prey eventually collapses, the Skahl descends for an easy meal.

This entry was made by community member, JustaDude. Artwork by TigerDude.